The Warrior's Lens: How Family History and Cultural Identity Shape Art

Part of the ETEBT Photography Project - exploring the deep connections between culture, identity, and creative expression

When we think about the forces that shape an artist's work, we often focus on technique, training, or artistic influences. But what happens when your creative vision is forged in the crucible of family history, cultural conflict, and personal discovery? For photographer Josh, whose work bridges the gap between Japanese and Filipino martial arts traditions, the answer lies in understanding that art isn't just about what you create—it's about reconciling who you are with where you come from.

From Survival to Art: The Making of a Martial Artist

The journey began not with artistic ambition, but with necessity. Growing up as one of the few Asian kids in a predominantly white Western Sydney school, bullying became a harsh reality for Josh. What started as a practical need for self-defense evolved into something much deeper—a lifelong exploration of discipline, culture, and identity.

"My martial arts journey began as a necessity," Josh reflects. Training with his uncle, an instructor instrumental in bringing Jeet Kune Do to New South Wales, provided more than just physical skills. It offered discipline, confidence, and a way to channel anger into something constructive. Weekend sessions around a lake became the foundation for understanding that martial arts was about more than fighting—it was about transformation.

The transition to traditional Shotokan karate under Sensei Jericho Eluna, a sixth or seventh dan black belt and former street fighter from Cebu, marked a deeper dive into Japanese martial arts. Despite parental skepticism—Josh's parents saw it as mere self-defense rather than art—he pursued his passion with unwavering dedication, even working as a kitchen hand from age 15 to pay for his own training.

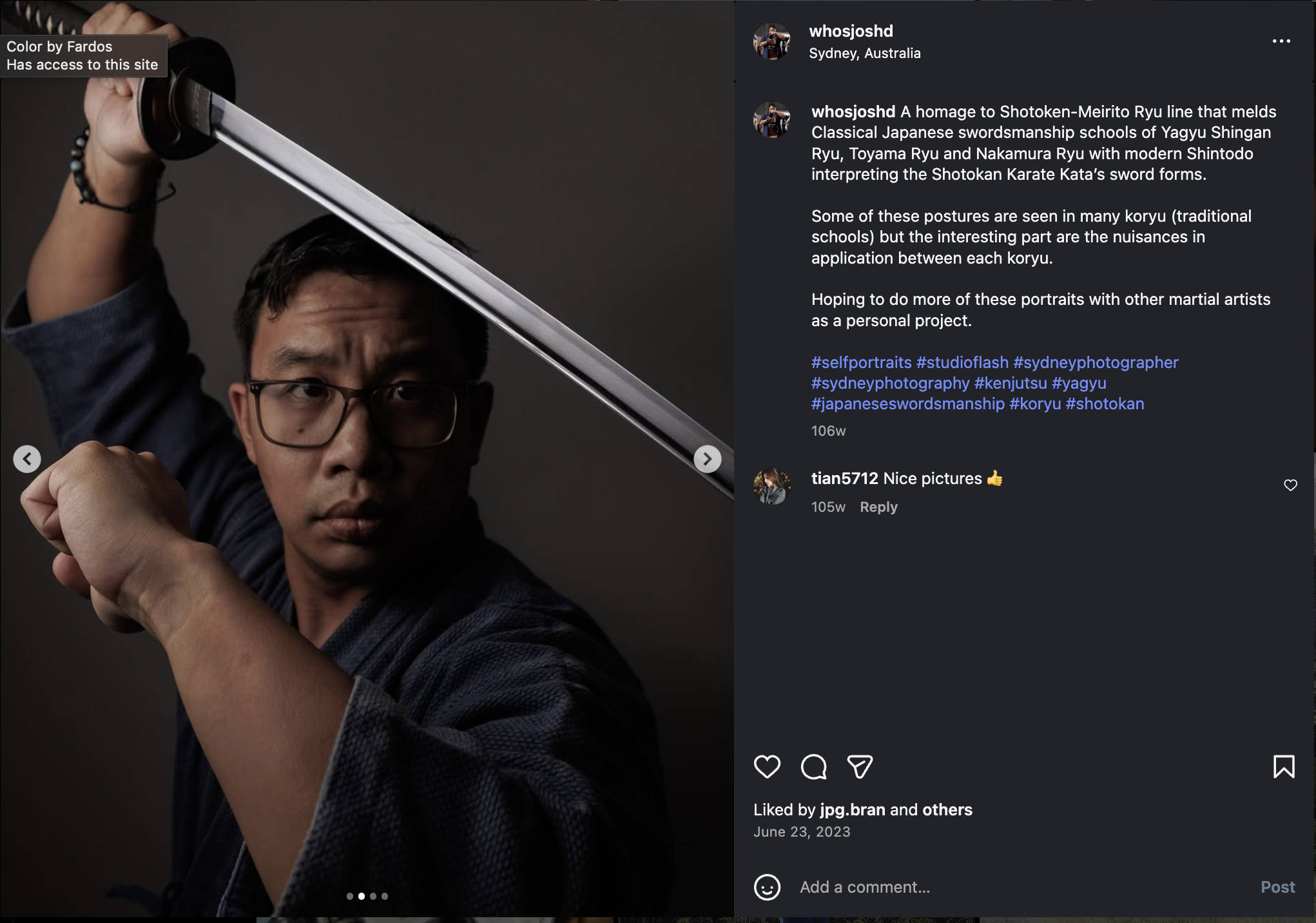

The Sword and the Sensei: Lessons in Precision

The allure of Japanese swordsmanship led to years of searching for the right teacher. When he finally found Sensei Andrew Melito, a foremost expert in Japanese swordsmanship in Australia, the experience was transformative. Sensei Molo's interview process—lasting three to four hours before acceptance—stood in stark contrast to typical Western Sydney martial arts schools that accepted anyone who paid.

"His movements with a wooden sword were sharp and precise, making the wood sound like it was cutting through the air," he recalls. This wasn't just about learning techniques; it was about understanding the philosophy behind the movements, the discipline required, and the respect demanded by the art.

The Tribal Wisdom of Filipino Martial Arts

A break from swordsmanship led to discovering Filipino martial arts (FMA), specifically Balintawak, taught by John Russell in Hyde Park. The contrast was striking. Where Japanese martial arts were structured, military-style with belt systems and formalized rituals, Filipino martial arts were tribal and informal.

"Grandmasters might be found in parks, smoking, with sticks on the ground, simply inviting you to 'play' to test your skill," he explains. This was the "fighting art of the masses"—efficient, survival-focused, and stripped of unnecessary ceremony. The approach was direct: "They show you, they don't tell you."

A Grandfather's Scars: When History Meets Identity

The most profound revelation came through family history. When his grandfather saw him in traditional Japanese gi and hakama with a short sword, the reaction was immediate and visceral: "The Japanese are evil. I fought them." Initially dismissed as the perspective of an elderly man, this statement would later reveal layers of complexity that would reshape his understanding of his martial arts practice.

During his grandmother's illness, his grandfather began sharing stories that had been buried for decades. He revealed he was a volunteer guerrilla fighter in Isabella, northern Philippines, under a U.S. colonel during World War II. The stories were harrowing—friends killed in ambushes, surviving a bullet wound by playing dead, resorting to machetes and bow and arrows when ammunition ran out. He was only 17 when the war began.

The complexity deepened with the revelation that his family ran a rice mill, supplying rice to the Japanese while he fought them covertly. Despite this deep-seated hatred, something remarkable happened in his grandfather's final days. When a Japanese veteran was admitted to the same nursing home as his grandmother, his grandfather eventually softened, even greeting the man with a smile—"some kind of peace."

The Photography Project: Honoring Both Sides of the Blade

This rich tapestry of personal history, cultural conflict, and martial arts mastery has culminated in a photography project that seeks to reconcile and honor both traditions. While engaged in fashion and editorial photography professionally, his personal work now focuses on the cultural side of martial arts and traditions.

"My project aims to show both this violence and the internal benefits, ritual, and history," he explains. "I want to draw comparisons between the military-style Japanese martial arts with their strict lines, uniforms, and precise movements, and the tribal, individualistic Filipino martial arts, where warriors defended their families with whatever they had."

The project's core philosophy is profound in its simplicity: one tradition is not better than the other. A Japanese Grandmaster in pristine uniform with a fine sword and precise posture is equal to a Filipino Grandmaster in basketball shorts and thongs, smoking a cigarette with a stick in hand. Both represent valid expressions of combat and survival.

"Japanese martial arts embody the 'ritual of violence' to conquer, while Filipino martial arts represent 'violence for survival,'" he notes. The photography seeks to capture this distinction while honoring both traditions without romanticizing the violence inherent in their origins.

Lessons from the Warrior's Path

His journey has crystallized several core philosophies that inform both his martial arts practice and his photography. First, never give an excuse to stop your passion—his biggest regret was pausing martial arts for university. Second, embrace both the good and the bad; martial arts is brutally honest about what works and what doesn't, providing clarity that contrasts with the subjectivity of photography.

Perhaps most importantly, "pain is the fastest teacher you'll ever have." This embrace of discomfort and challenge has become central to his approach to both martial arts and art-making.

Where We Come From: The Foundation of Art

Growing up in Western Sydney instilled a heightened sense of awareness that continues to inform his work. While protected by his religious community, exposure to darker realities through work and volunteerism taught him to navigate potentially dangerous situations, always aware of surroundings, exits, and the intentions of others.

This awareness—not paranoia, but conscious attention—has become fundamental to his artistic practice. It's about being attuned to who is in the room, what stories need to be told, and how personal history shapes creative expression.

The Intersection of Culture and Creativity

His story illustrates a fundamental truth about artistic expression: our most powerful work often emerges from the intersection of personal history, cultural identity, and creative passion. His photography project isn't just about documenting martial arts—it's about reconciling complex family history, honoring multiple cultural traditions, and finding peace through artistic expression.

The warrior's lens sees beyond technique and form to capture the deeper truths about identity, survival, and the human capacity for both violence and peace. Through his camera, he's not just documenting martial arts; he's creating a visual bridge between cultures that have been both at war and at peace, showing that understanding where we come from isn't a burden—it's a profound source of insight and inspiration.

In the end, his work reminds us that the most compelling art often emerges from the most complex personal journeys, where the artist's identity, history, and passion converge to create something entirely new while honoring what came before.

This feature is part of the ETEBT Photography Project, which explores how cultural identity and personal history shape creative expression. Each conversation reveals the deep connections between an artist's background and their work, showing how understanding our origins can become a powerful source of artistic inspiration.